News

Possibilities for the future of the city

Posted 20 04 2023

in News

Mark Southcombe, Hannah Hopewell and Isaac Velasco present an edited discussion on the process and findings of ‘Re-imagining Mass Housing’ and ‘Re-imagining Just Landscapes: Pito-one’ – two multi-scaled, urban architecture and landscape design research studios undertaken in 2022 by Te Kura Waihanga Wellington School of Architecture March students in collaboration with Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Hutt City Council.

In early 2020, the Wellington School of Architecture began two studio projects in

collaboration with Te Awa Kairangi Hutt City Council that brought specialist professionals and council officers with expertise in urban design, sea-level rise, housing and mobility together with students to expose academic studio design inquiry to the live technical complexities of city making. The collaboration grew from a shared ambition to generate diverse, design-led thinking, re-imagining possible future living and built environments. We were motivated to align situated university studio projects with council imperatives and activate community discussion on potential built environment legislative changes and significant climate impacts faced by the city.

Hutt City Urban Design Team Lead Isaac Velasco said the opportunity allowed new dialogue about re-imagining the city with a new generation of citizens: “those citizens that, in the future, will take important decisions, with more human-centred, indigenous and environmental design approaches”.

The Wellington School’s architectural and landscape architecture design studios at master’s level pursue areas of disciplinary specialisation, stretching students’ strategic, conceptual, spatial and technical competencies in complex contexts. Imagination and visioning form an integral part of this skill set, where students’ abilities to project futures through the agency of disciplinary knowledge and change correlates with their skills in navigating the complexity of the present. Converging with these pedagogic demands, the studios embodied the emerging opportunities for urban change in Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai.

The Re-imagining Mass Housing architecture studio responded to Isthmus’ RiverLink Urban and Landscape Design Framework, “a transformative project for Lower Hutt City, envisaged as a catalyst for the revitalisation of river and city, people and identity”. An interstitial, left-over, predominantly residential site, likely to be subject to change, was identified in Melling. The site was ideal as a place to explore housing intensification. It is adjacent to the motorway, railway and river, and has proximity to the proposed railway station, a mixed-use area, new high, landscaped stopbanks and a proposed pedestrian bridge connecting across the river to the city centre.

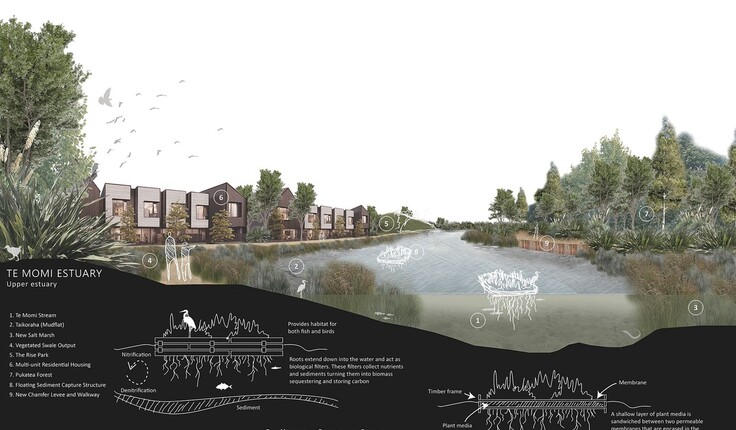

The Re-imagining Just Landscapes: Pito-one landscape architecture studio was situated in the low-lying suburb of Petone, where Te Awa Kiarangi Hutt River meets Te Whanganui-a Tara Wellington Harbour. Petone manifests considerable climate risk, vehicular dominance, frequent flooding and poor water quality alongside a nexus of social and spatial concerns, making it an ideal site to test climate-adaptive techniques alongside public realm regeneration and housing uplift. Aligning with Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Hutt City Council strategic objectives of growth and intensification, the projects aimed to re-imagine Melling and The Esplanade, Petone, as safe, resilient, just and humane living environments.

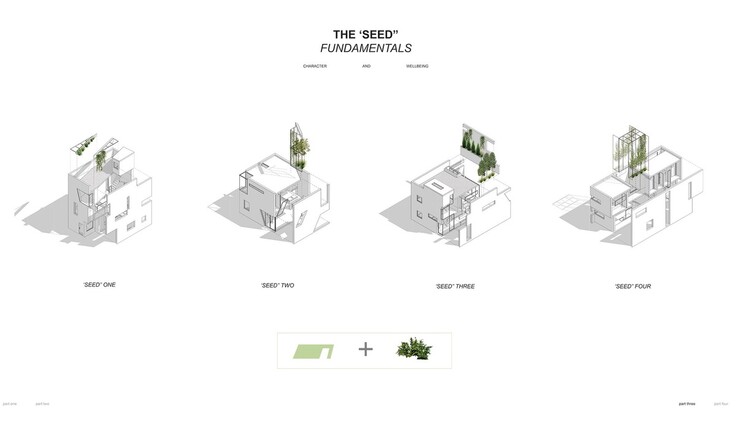

The Re-imagining Mass Housing brief was generated from associate professor Mark

Southcombe’s ongoing housing density research agenda. It was “an experimental, future-focused, design-led housing re-imagining, informed by single-site, high-density Japanese housing precedents relevant to our Aotearoa preferences for single site housing”. It also responded to the Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS) enacted by the government to increase housing density as it affected a part of Hutt City. The new standards create an exciting new context, with opportunities for innovative architecture, but risk formulaic, repeated, speculative housing at maximum densities and minimum standards to maximise development profits. So, the studio was also a critique of speculative housing and “the dumbing down of housing design and associated negative environmental and social effects”.

Lecturer Hannah Hopewell’s Re-imagining Just Landscapes: Pito-one brief applied her Relational Landscapes research agenda, testing regenerative landscape-led urban development approaches. With a lens of interconnectedness, land was focused less as territory and rather as the living field for reciprocity or as social ecology. “This foregrounds mauri, ‘the bonding element that holds the fabric of the universe together’, in landscape architectural practices to open students’ envisioning beyond prevailing instrumental or ‘mitigative’ imperatives.” It allowed students to connect the ways in which past land confiscation and modification continues to influence the present. Approaching Petone in this way ambitioned students to engage design creatively and critically as a positive agent in the social and environmental justice of urban environments. Climate-adaptive innovations were key to this advance in the re-imagining of heterogeneous social-spatial-environmental relations and new ways to live together amidst a rapidly changing world.

Benefits of engaging in these "Live" Projects

The partnerships were offered by Head of Urban Development Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Hutt City Council Dr Becky Kiddle, who saw numerous potentials in aligning student design research with council aspirations. Testing the capacity of collective architecture and climate-adaptive landscape architectural design research studios through situated projects concurrent with socially and environmentally just, land-based change would not only expose students to council expertise on a live project but also support Council in the development and refining of priorities and policy responses.

The situated projects allowed students to participate in the disciplinary environments of which they are a part and engage with limitations and opportunities for change. Design responses can be critically compared to realised projects and, when seen together, can create a range of possible alternative future visions. The students’ participation in council processes included council provision of resources and an evidence base, briefings with council staff, and participation in public engagements.

Critically, the projects allowed Council to participate in supporting ‘thought leadership’ and leverage democracy in action with its community, yet avoid being caught up in the risks associated with proposing or owning any specificity of ideas on urban change. The projects’ public dissemination as exhibitions modelled a positive way forward for community engagement.

Pros and cons of this "Live" Project

The benefits for the student body and the Council of aligning pedagogical and council interests included students offering an ability to reach into the future and explore the unforeseen without detailed economic development constraints. Design findings proved valuable as provocations to expand thinking within the council processes, as well as more formally, as public consultation tools, fleshing out visions that embody implications of policy and elicit planning and public responses. On the downside, student experimental work is often technically untested, and timing can prohibit meaningful interface with other built environment disciplines. Mana whenua engagement is also impacted by timing and cannot equitably occur unless prior connections exist, and planning is advanced well ahead of the studio time frames.

Key Challenges and how they were resolved

The landscape architecture project was one of monumental complexity. Students wrestled with how to scope and scale their design process. Initiating climate-adaptive responses alongside social-spatial change in Pito-one Petone unearthed a multitude of interwoven issues and opportunities across ground contamination, increased flooding, water quality, sea-level rise, erasure of mana whenua identity, vehicular dominance, unsafe pedestrian environments, land use change, and housing affordability and intensification. Working from a relational paradigm, thinking about the technical alongside the social, helped to move students towards landscape design as a democratic mechanism and scope their interventions accordingly.

Working with council staff and their guiding documents, such as the 2017 Petone 2040 urban plan, was critical to prioritisation and sharpening the relevance of student investigations. Council supported the live studio approach by sharing accurate and updated data, technology, and plans and policies for research and analysis, helping students to frame their approaches and be more pragmatic in their designs and proposals.

The main challenges for the architectural project included scope and scale: aligning Hutt City and university aspirations. Pedagogical intentions included a desire for students to develop their own design research agenda around the project while resolving issues around design for density. Hutt City was primarily focused on the effects of urban-scale planning issues associated with its proposed major changes of infrastructure as they may play out over time. They valued access to student visions representative of a younger vision for the city. The project brief was set to operate on both wider urban and residential precinct scales, beginning with macro-planning implications that resulted from the Hutt City’s RiverLink project and moving to site scale and implications of the MDRS within the precinct. Opportunities for intensified infill housing were tested to two stages and time frames: medium-density infill followed by a longer-term, higher-density vision.

Designed outcomes and effects of the projects

For the students of landscape architecture, navigating complexity yet eliciting a coherent relevant design proposition marked a significant advancement in their design education. The 23 students responded individually, each with their version of what safe, resilient and just environments might look like, yet the studio was grounded in collaboration. A Miro board was used to share fieldwork and site research, enabling an ecology of ‘analysis’ as a live resource for the course duration. This proved powerful in understanding the situated interconnectedness of issues, prompting students to think across realms often held apart or erased. To round out the predesign phase, a cultural and environmental map of Pito-one was collectively drawn to act as the project’s shared expressive ‘evidence base’.

At the Strategic Development Framework phase, students found multiple regenerative opportunities by strategically aligning sea- level rise adaptation, coastal habitat creation and public realm regeneration with flood adaptation, housing densification and refined local movement networks. Students found ways to re-route heavy traffic from the Petone Esplanade and transform the road into a mixed- use, pedestrian-dominant environment with strong connectivity from the beach to the town centre.

In the Developed Design phase, the bulk of design testing focused on hydrological issues and biophysical realms to support a resilient, biodiverse future. “The demands of sea-level rise and increasing flooding risk saw innovation in constructing and adapting hydrological and terrestrial living systems across the riverine systems of Te Awa Kairangi as a technical and a socio-spatial concern.” Examples of this included: soil-swapping remediation, kelp farming as a carbon sink, storm-surge moderation and restoration of mahinga kai, detention wetlands, habitat creation from food webs mapping, place- based revegetation, dune land extensions and more. Landscape-based living interventions were shown to be essential to the sustainability of Petone’s re-imagined built form, public realm and movement networks.

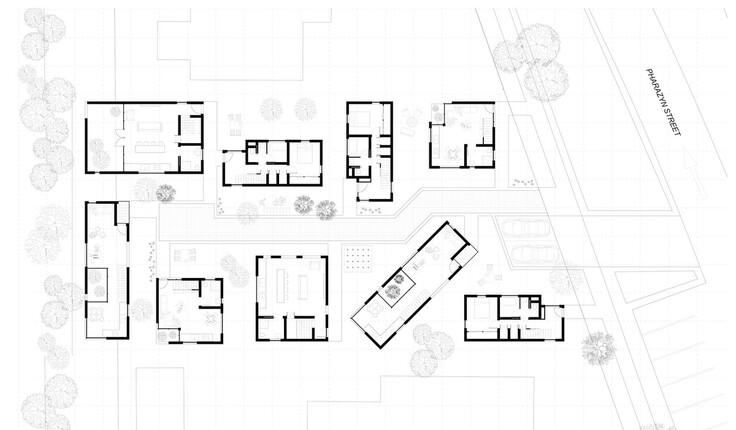

In the Mass Housing studio, a Macro Plan vision was created, consolidating student individual analysis and plans in a joint workshop with students and Hutt City Urban Design Team Lead Isaac Velasco. This collective urban vision was the basis for site-scale projects that followed.

Finally, a collective student model combined all student projects to create a compelling re-imagined Aotearoa housing environment with a mix of individual and shared-site housing. The vision contrasts with the standardised cookie-cutter character of many of our current medium-density-housing urban environments. It demonstrated that diverse, humane, environmentally sensitive housing environments can be created with equal attention given to the design of architecture and the spaces between houses and sites. The collective vision is a compelling argument for increased planning flexibility in housing scale and typology paired with design quality to achieve maximum densities and high-quality living standards.

The urban-scale precinct planning found increased opportunities for urban intensification because of the precinct’s semi-discrete, quirky ‘island’ character, both well connected to and clearly separated from the rest of the city. These qualities facilitated greater housing intensity than can easily occur in the urban fringe. The collective macro-planning identified some key moves that informed the current Hutt City urban growth plan process. These moves include: the potential for local increased density, Pharazyn Street as a shared-space, single-direction, local laneway, focused on pedestrian, micro-mobility and service access, potential for pedestrian permeability between and through sites to Te Awa Kairangi Hutt River, and the benefits of collaboration between neighbours for the negotiation of density on boundaries and shared access and shared open spaces.

The local housing cluster scale design work created a series of beautiful, refined and unique contemporary high and medium-density housing designs that model alternative ways of living at density. A key realisation was for careful consideration and balancing of site landscape design with housing interior design. High levels of solar access, privacy and amenity can be created at density through the design and careful curation of outlook and spaces between buildings in relation to one another. This principle has great promise for the relationships between buildings on sites but, also, for larger redevelopments, where collaboration on massing locations across boundaries can significantly increase the quality of spaces at the edges of, and between, sites.

As noted by critic Gerald Parsonson, these qualities are evident when ground-floor and site planning are both evident together on site drawings. Several student projects combined low-rise, four or five-floor apartments with three and two-floor housing models, demonstrating that density and variation in the built environment can be moderated by variation of building types and scale. The benefits of this approach are obvious to designers but rarely possible in practice, restricted by well-meaning planning rules that are prescriptive yet too general to encourage design massing diversity at site scale. Students also prioritised provision of shared, local coworking and community facilities in many of the proposals, augmenting efficient space design and suggesting mixed-use is important to help reduce travel and improve the lifestyles, convenience and sustainability of suburban environments.

Role of reviews and exhibitions in relation to design projects

The reviews, during and at the end of the project, and the exhibitions were key means of communication between the Wellington School and Hutt City Council, and with the local community. The final reviews for the Re-imagining Mass Housing project were in the form of a public event in the Lower Hutt Little Theatre, with contributions from the Hutt City planning team and Parsonson Architects. Here, the stage lighting communicated the student model architecture beautifully, and the students were highly engaged and responsive with very professional presentations.

The reviews were followed immediately by a public Re-imagining Mass Housing exhibition in the Hutt City library in association with the Re-imagining Just Landscapes: Pito-one exhibition, complete with a formal opening and celebration event. There was also a separate public floor talk associated with the exhibition, engaging with the local community. These public interactions opened discussions with planners and residents about the challenges, effects and opportunities associated with climate change adaptation and residential intensification. Feedback from the community helped shape Council’s recent structure plan processes and ongoing promotion will generate discussion of design issues around climate change adaptation and residential intensification.

What could have been done differently and what's next?

A council is a multidisciplinary organisation and its citizens have wide and diverse interests that impact public projects in the urban realm. As these were theoretical projects, the strengths were in abilities to start fresh, challenge norms and flesh out visions for alternative possible futures. This is helpful for stimulating discussion and can also be challenging to the status quo where there are likely to be future changes on the horizon, which are still taking shape and don’t have defined time-scales. There were some political implications associated with the projects’ timing in relation to the local body election cycle, which limited elected representatives’ time availability and increased sensitivities about possible implications of climate change impacts or increasing housing densities.

In future, council officers and politicians would be involved earlier in the discussions, to enable even greater targeting of each project towards political and planning issues and the design implications of these. Some earlier engagement with the Council’s communications team and wider advertising would have helped increase community engagement.

To conclude, the students’ experimental design work generated an alternative tempo to normative council project development. Velasco welcomed the ability of student knowledge creation to be disruptive or tangential, with its diverse and alternative propositions, and saw it as positive in its facilitation of community discourse. Velasco likens Council’s role here to that of a bridge, enabling connection and conversation across its communities.

Mark Southcombe FNZIA is an Associate Professor at the Wellington School of Architecture where he leads design-led research and studios. Dr Hannah Hopewell is a tangata Tiriti educator and practitioner whose creative and critical research practice focuses on landscape-led urbanism. Isaac Velasco is the Urban Design Team Lead at Hutt City Council. He leads technical work for the Urban Growth Plan.

Share

14 Apr

NZILA Board nominations close tonight

Read the insights from current Board members

What does the current Board have to say about this opportunity? REMINDER: Board Nominations close tonight, 14 April, 11.59pm We …

08 Apr

Update from Environmental Legislation Working Group

RMA Reforms and NZILA Wānanga

Our understanding of Spatial Planning and in creating well-functioning environments is more deeply considered than simply green fluff - the …

02 Apr

Follow up from the virtual IFLA World Council (22 and 23 March)

Did you attend the virtual IFLA World Council held last weekend? Presentations and ReportsThese can be found here. RecordingFor those …

Events calendar

Full 2025 calendar